The World Chess Federation in Las Vegas, NV is involved in a dispute over trademark infringement. The web site for the World Chess Federation has a profile of its founder Stan Vaughan which includes this claim:

Grand Master Stan’s expertise as a cryptanalyst led him being noted for having solved two of the most important previously unsolved ciphers in the world: The Shugborough Hall Monument cipher for which he had received an award from the Reform Club, and the Zodiac Serial Killer 340 character cipher. Stan was also a National Trivial Pursuit Champion of 1986.

I cannot find any references that mention his solution. Does anyone know anything about it? I am attempting to contact Mr. Vaughan to see if he will give more information about his solution.

Do you think you’ve solved the Zodiac 340 cipher? University of North Texas professor Ryan Garlick has written a handy guide that you should read. Once featured on the National Geographic documentary “Code Breakers“, Dr. Garlick has studied the Zodiac ciphers for many years, and has even recruited his students to try to solve them. He knows how to spot bad solutions, and his guide shows you how you can easily spot them, too. Bad solutions usually have common symptoms, such as symbols representing multiple letters, liberal use of anagramming, gibberish that needs to be highly interpreted, frequent changing of the cipher keys, and the use of fake patterns such as numerology. To his guide I would add my litmus test: If your approach can generate many different and equally compelling plaintext messages, then you can’t prove your approach is the one used by Zodiac to encrypt his message. The best example is the known solution for the 408-character cipher. There is only one overall solution that can be generated with that method, and it results in a coherent message requiring no elaborate manipulations of the key. You could quibble over some misspellings and mistakes, but they do not result in a brand new message that it totally different from the known solution.

Kevin Fagan recently wrote that many theories about the Zodiac Killer case are still being made, despite the case being 45 years old. If you have cracked the cipher, stand apart from all the bad ideas by making sure your solution does not show the problems mentioned in Garlick’s guide. Then maybe you are on the right track. Good luck!

Much has already been written about the dubious content of the recently published book The Most Dangerous Animal of All: Searching for My Father . . . and Finding the Zodiac Killer by Gary L. Stewart and Susan Mustafa. It joins a crowded pantheon of weakly supported books, and yet went on to make a profitable appearance on the New York Times bestseller list for non-fiction eBooks.

Michael Butterfield does a good job of pointing out the major problems with the evidence presented in Stewart’s book. There is also a lengthy thread on Mike Morford’s forum, and many posts on Tom Voigt’s forum. You can look at Stewart’s evidence and judge for yourself.

But here I will focus on the the book’s claims about the ciphers. The authors write that Stewart’s sleazy father, Earl Van Best Jr., was the Zodiac Killer, and his name appears in three of the killer’s cryptograms. The authors suggest that this is proof that their suspect is indeed the Zodiac killer.

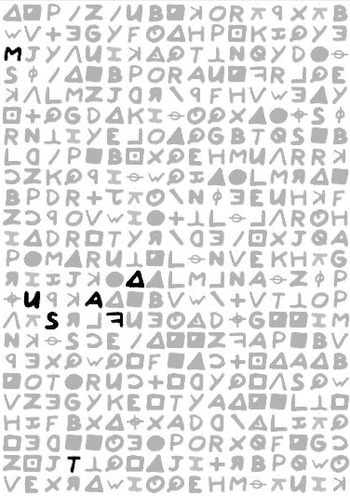

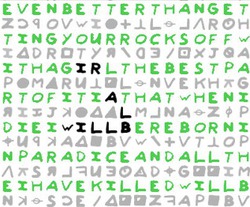

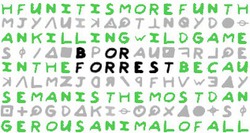

Let’s look at how they found his name in the Zodiac’s 340-symbol cryptogram:

Using the kanji style of writing he had learned as a child in Japan, [Earl Van Best Jr.] began on the right side of the page, arranging letters and symbols in vertical columns. Instead of a coded message, he included his full name, written backwards.

…

[One of New York’s Christian literary agents B. G. Dilworth] pulled up some images of the ciphers on his computer and at random began studying the 340 cipher, looking for my father’s name. He began by looking for the name Best.

…

Working his way from right to left backwards across the cipher, he found the name, Earl Van Best Junior. Van had put one letter of his name in each column.

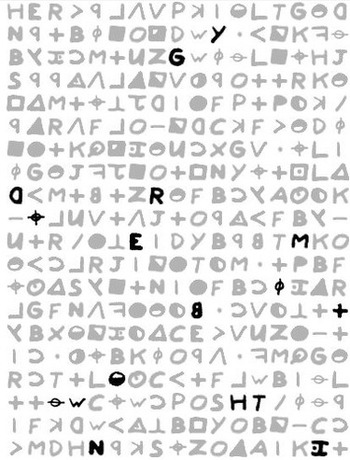

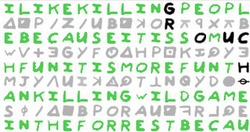

Here’s what Dilworth’s discovery looks like:

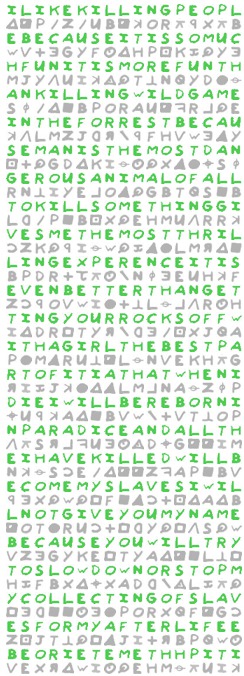

Each column has one symbol marked. Here’s what they look like when you write them out from left to right:

But let’s write them from right to left instead, as Dilworth found them:

So, we’re getting closer, but it still does not look quite right. To overcome this, Dilworth allows some symbols to resemble other letters. For example, he treats the half-filled circle as the letter E. Here are the symbols with Dilworth’s interpretations:

Dilworth indulges in a bit of freedom with his approach. The problem, though, is that it causes at least hundreds of thousands of other names to appear in the ciphers. How can you know for sure that Earl Van Best Junior, a name among thousands, is the correct one? You can’t, unless you assume that you’ve already correctly identified your suspect.

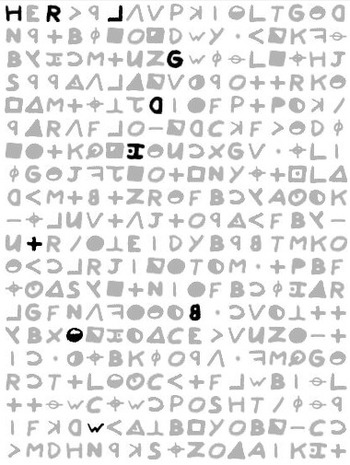

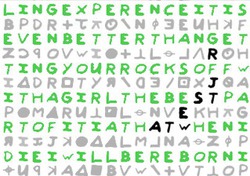

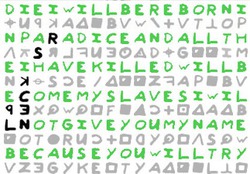

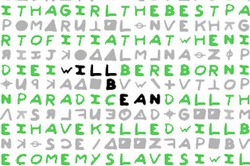

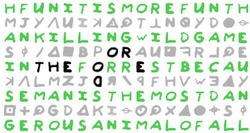

Here’s a small sampling of the abundant names you can find using the same approach.

Timothy B. Greenwood |

Clifton D. Pritchett |

Carl B. Powell Junior |

Earl Vasquez Junior |

In fact, using Dilworth’s method, you can find many other similar Earls, such as: Earl Van Cook Junior, Earl Van Bell Junior, Earl Van Diaz Junior, Earl Van Cole Junior, Earl Van West Junior, Earl Leo Best Junior, Earl Bob Best Junior, Earl W Powell Junior, Earl B Little Junior, Earl T Howell Junior, Earl Clayton Junior, Earl Clifton Junior, Earl Wendell Junior, Earl B Patton Junior, Earl C Abbott Junior, Earl L O’Neill Junior , Earl a Osborn Junior, Earl O Hayden Junior, Earl C Albert Junior, Earl V Madden Junior, Earl Tolbert Junior, Earl F Bowden Junior, Earl Colbert Junior, Earl Boswell Junior , Earl Conklin Junior, and on and on and on. They are all appearing due to coincidence. Earl Van Best Junior is appearing due to the same kind of coincidence.

The book says:

To assure himself this was not a coincidence, B. G. used the same method to try to find his own name. It wasn’t there

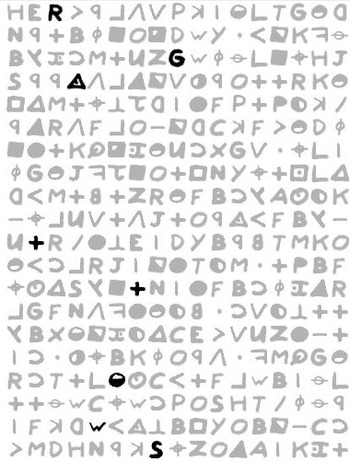

He must not have looked hard enough, because it is there:

B.G. Dilworth |

“Dilworth” even appears in the 408! |

Gary Stewart himself appears |

Gary Stewart’s full name appears in the decoded 408 |

Even his co-author Susan Mustafa appears in the 408 |

Dilworth also says:

He then looked … for more common names like Jane Brown and Mary Smith. He couldn’t find any first and last names in the same sequence

Once again, he didn’t look hard enough. Jane Brown can be found if you apply the method from top to bottom, and other common names are easily found:

Jane Brown |

Betty Scott |

Dorothy Collins |

You can try it for yourself with this search gadget. You can also look at the 170,000 names I’ve found so far here (male names) and here (female names).

The book also says:

Even though the cipher had been decoded, they couldn’t take the next step of deciphering the killer’s name, because they didn’t know what name to look for.

Unfortunately, what this really means is: If you start with a name ahead of time, you can force it to appear within the cryptograms. This is how so many unreliable solutions are conjured from thin air. We see it repeatedly, and the pattern is usually this: The solver tries to generate a specific name, and eventually figures out a technique to make it appear. But the technique usually generates many other names. Since the solver has a strong desire to promote their suspect, all the other names are conveniently ignored.

You still need to prove that your solution isn’t just appearing by chance, like a face in the clouds.

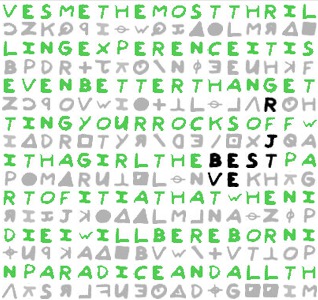

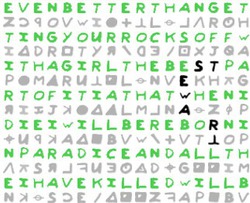

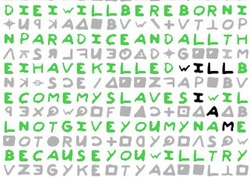

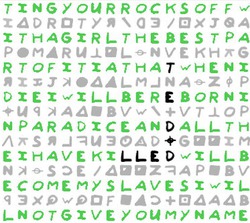

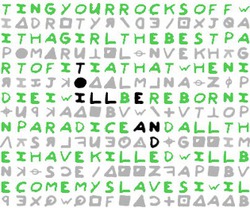

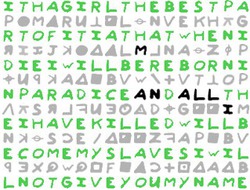

Now let’s look at the authors’ claims about the 408 cipher:

I found a version on the Internet where the decoded message had been typed above the Zodiac’s cipher. I approached the three sections of the cipher as if they were a seek-a-word puzzle, looking at a particular letter and then looking vertically, diagonally, and across for my father’s name.

I saw it right away, plain as day: EV Best Jr.

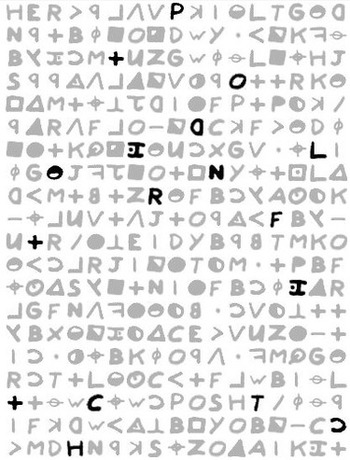

Here’s the 408 with the decoded message printed above the cipher:

And here’s where he found E.V. Best Jr:

Notice how the name is permitted to flow in multiple directions, and can skip a symbol. As expected, that name is appearing purely by chance. Many other names can be found by chance as well:

Stewart |

A.T. West Jr. |

H.T. King Sr. |

N.L. Peck Sr. |

William |

Milton |

Wanda |

Will Blair |

Will Bean |

Theo Nash |

Lee Allen (Arthur Leigh Allen?) |

Ted O’Dell |

Ned Williams |

Rob Forrest |

Theodore (Kaczynski?) |

Dan Eilliot |

(Richard) Gaikowski |

(Fred) Manalli |

F(red) Manalli |

|

|

Again, there’s no way to accept “E.V.Best Jr” as a correct interpretation unless you already accept Stewart and Mustafa’s story.

Lastly, Stewart attempts to connect their story with Zodiac’s 13-letter cryptogram:

My father then included a new cipher with thirteen characters, including letters and symbols — the exact number of letters in Earl Van Best Jr.

The only connection there is that the length of “Earl Van Best Jr” is the same length as the 13-letter cryptogram. This is an extremely weak connection, since there are millions of names that are thirteen letters long. And the authors don’t bother to explain what any of the symbols mean!

I don’t doubt that Stewart’s father was a bad man and committed many terrible acts. But Stewart and Mustafa have tried to convince us that simple coincidences in the ciphers are proof Van Best was the Zodiac Killer. Stewart has made many rounds in the media to promote his book. His efforts were very successful – his “non-fiction” book sold many copies. But both the media and his publisher remain agnostic over the truth of his claims, sadly reinforcing the profit cycle of folklore and misinformation.

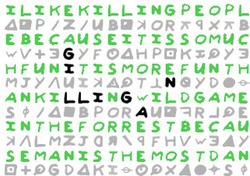

Deborah Silva unearthed these articles from May 1970 issues of the Oxnard Press Courier:

|

|

A woman claimed to have found the name “Manto Mokhenea” in the Zodiac’s unsolved “My name is” cipher.

The name doesn’t quite fit into the cipher (if you assume it is a substitution cipher like the 408). If you make an adjustment, such as “Monto” instead of “Manto”, then the letter counts are correct, but you have to shuffle the letters to make them fit into the cipher text. As we know, this approach is not useful, since it generates millions of possibilities that you can’t narrow down.

Still, I wonder where she got the name “Manto Mokhenea”. It looks more Hawaiian than Russian to me!

UPDATE: A reader points out: Manto Mokhenea – just looks like the “my name is” cipher backwards

(Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5)

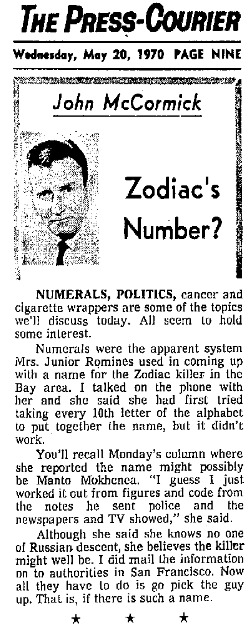

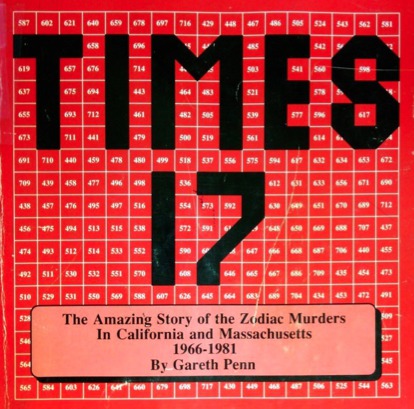

A generous Zodiac researcher loaned me a copy of Gareth Penn’s hard-to-find book Times 17: The Amazing Story of the Zodiac Murders in California and Massachusetts, 1966-1981. Gareth Penn is one of the most prominent and prolific people among the many who have inserted themselves into the folklore surrounding the Zodiac case.

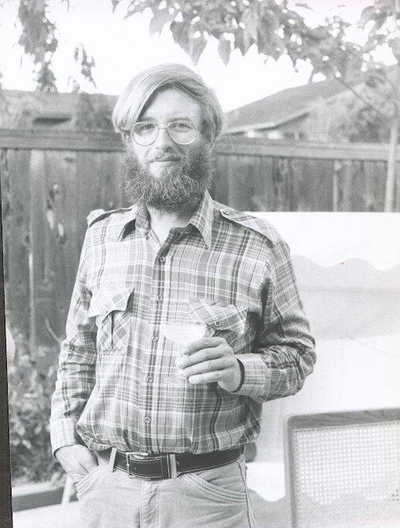

Gareth Penn (Credit: Mike Martin)

In 1987, Penn self-published Times 17, a collection of his sprawling essays, filled with well-written but delusional speculations connecting Berkeley professor Michael O’Hare to the Zodiac killings. Repeatedly dismissed by authorities, Penn’s claims span almost 400 pages. The book is filled with elaborate mathematical ideas which superficially appear rational, but fall apart quickly when examined. Penn’s most abundant trick is to use math to simultaneously generate and disguise random coincidences. First, he sets up basic systems of mathematical operations that create new information from the Zodiac’s correspondences and other facts surrounding the case. Then he plucks out the interesting bits of new information generated by his tricks, and ignores all the other uninteresting coincidences. This confirmation bias approach is shared by many similarly misguided amateur sleuths and codebreakers. Penn’s complicated mathematical procedures create a barrier for most readers, making his claims tedious to analyze and challenge. For an example, see my previous article about Penn’s letters to the popular Scientific American writer Martin Gardner. There you can see why Penn’s “binary Morse” system quickly falls apart: Morse code has a hell of lot of different interpretations when you let the codes run together.

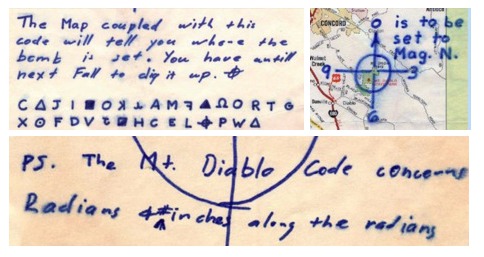

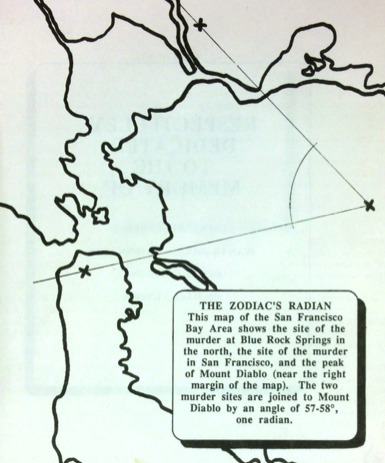

Times 17 also features Penn’s “radian theory“, in which two of Zodiac’s killings form an angle of approximately one radian with Mount Diablo.

Map code and clues in Zodiac’s correspondences

Penn’s radian observation

It’s arguable whether this is by design by Zodiac. At the least, it’s an interesting observation. But throughout Times 17, Penn takes the idea to ridiculous extremes, connecting his mathematical games to angles formed by key words and elements of Zodiac’s correspondences. Penn spreads the interesting observation thinly across a great deal of poor reasoning.

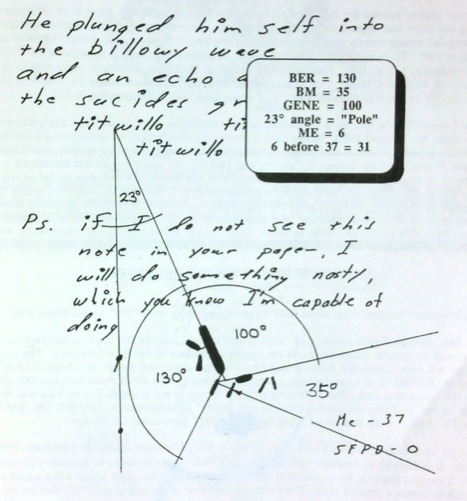

Example of Penn’s application of pseudo-mathematics and angles to Zodiac’s letters

Penn’s bizarre behavior led some to think he might be the Zodiac Killer himself. And like Zodiac, Penn even has his own copycat. Former postal carrier Raymond Grant also self-published his own book filled with “proof” of Zodiac’s identity. His book is filled with many of the same mathematical coincidence generators employed by Penn. For many years, Grant has been arguing that Penn was part of a larger team which included Michael O’Hare, O’Hare’s mother, and Penn’s father. Grant claims he discovered and disrupted the catastrophic “Terminus Event“, the culmination of the group’s “Zodiac Project”. On web sites and online forums, Grant repeatedly tried to share his theories, which were met with strong criticisms. This led to a pattern of Grant authoring many lengthy responses and rebukes, only to be followed by their removal because of his frustration with other Zodiac researchers.

Grant describes discovering the “Terminus Event”

Penn and Grant seem to be intelligent, capable writers. But any serious analysis of their claims will lead you to question their sanity. Or at least their motivations. The study of the irrational crimes of the Zodiac killer has branched into an entire forest of irrational behavior, fertilizing an expanding mythology, like UFO enthusiasts have done by filling in the blanks on mysterious events in the sky.

You can now read the entirety of Times 17 online, if you want to subject yourself to the experience. The book is split into five parts, and can be viewed at the following links:

Times 17 – Part 1 of 5

Times 17 – Part 2 of 5

Times 17 – Part 3 of 5

Times 17 – Part 4 of 5

Times 17 – Part 5 of 5

You can also download the entire 100 megabyte PDF here: times-17-full.pdf. (UPDATE: Thanks to zodiphile, the book is now available in epub and mobi formats for reading on mobile devices). For more of Penn’s writing, read his Ecphorizer articles, or his followup book The Second Power (read it online here). He is also reportedly working on a third book. And, you can still visit Penn online at his blog, where you will only find the occasional bizarre posting of his cryptic puzzles.

Be sure to read Michael J. Martin’s comprehensive and fascinating article which goes into a deep exploration of the Gareth Penn saga. O’Hare himself has also written an article about his experience with Penn. Michael Butterfield has also written a lot of interesting material about both Gareth Penn and Raymond Grant.

Film reviewer Mike D’Angelo once wrote, “I think the [Zodiac] movie erred in selecting author Robert Graysmith as its source and nominal protagonist. Zodiac buffs know well that the true obsessive is a fellow named Gareth Penn.” Have a look at Times 17 and see if you agree.

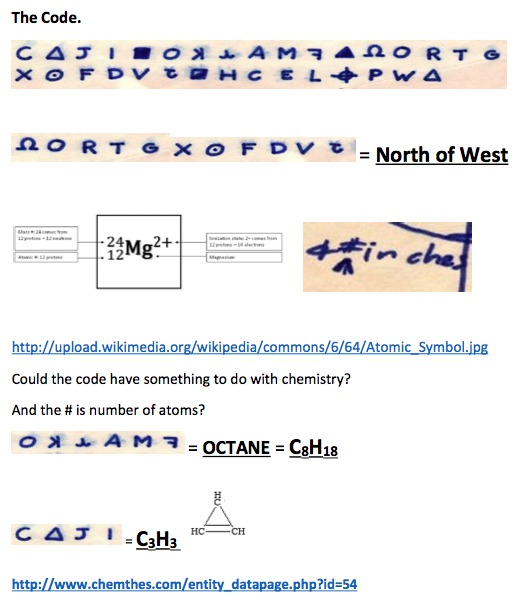

Crypto enthusiast Nick Pelling recently posted this interesting article about two Swedish engineers who developed a theory about the Zodiac’s unsolved 32-character “map code”.

I agree with Nick’s assessment that the theory is ridiculously convoluted, and that it cannot possibly be correct.

The map code is the most difficult of Zodiac’s cryptograms to solve, because only three of its symbols are repeated. With so many unique symbols, numerous solutions can fit into those 32 characters. By itself, a solution to the cryptogram is impossible to validate. But maybe someone can discover some indisputable connection between the map and the code. Keep trying!

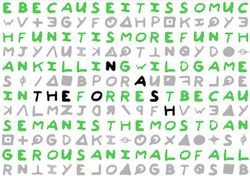

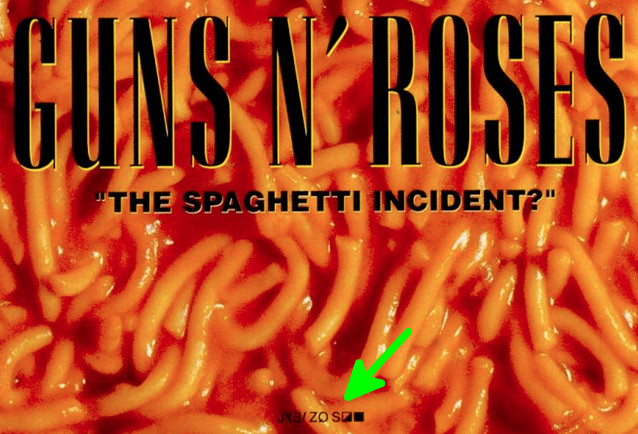

Zodiac’s cryptogram symbols made a surprise appearance on The Spaghetti Incident, an album from the hard rock band Guns N’ Roses:

It contains a valid message. Hint: Use the 408’s key.

Click here to see a forum post with more background information on the album and cryptogram.

I had the pleasure of attending this year’s Cryptologic History Symposium, held on Oct 17 and 18 in Laurel, Maryland. The event is organized every two years by the non-profit foundation that supports the NSA’s National Cryptologic Museum.

The proceedings were filled with dozens of fascinating talks by noteworthy professionals in the world of cryptology, and I met several interesting and colorful personalities. Here are some highlights.

NSA Deputy Director John C. Inglis kicked off the symposium with his keynote talk, in which he spent a lot of time defending the NSA in light of the numerous unauthorized disclosures by Edward Snowden of the NSA’s secret and controversal surveillance programs.

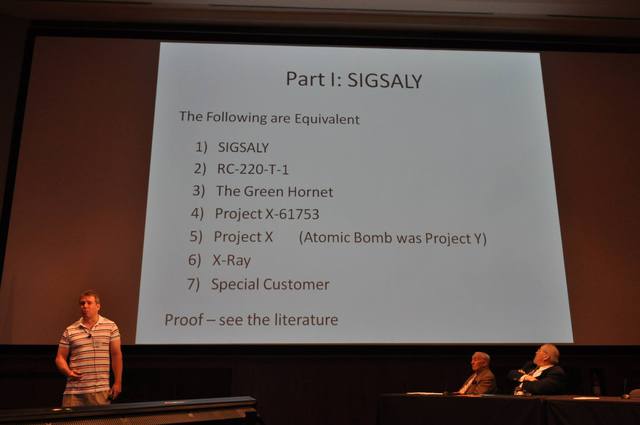

York University professor Craig Bauer told a fascinating tale about famed computer scientist Alan Turing’s work on SIGSALY, a telephone voice scrambling machine developed during World War II. Created before the digital age, the machine was humongous and required carefully protected phonograph disks to store the cryptographic keys consisting of random noise.

I spoke with Dr. Bauer and learned that he had included the Zodiac Killer in an interesting talk he gave about famous unsolved codes and ciphers. He’s also working on an upcoming book about this topic. Videos of his talk are available on Youtube:

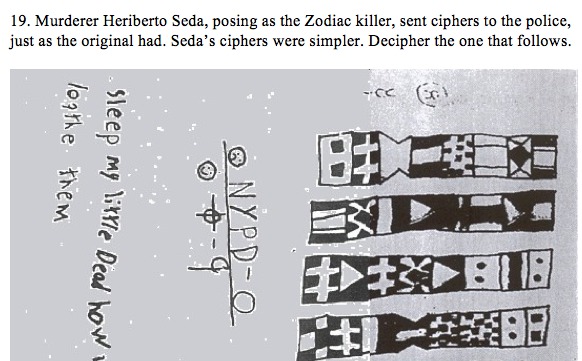

Click this link to go directly to the Zodiac portion of his talk which starts 12 minutes and 32 seconds into the video. He gives a brief summary of the case, and touches on Gareth Penn’s radian theory and the New York Zodiac copycat killer Heriberto Seda.

He even gave Heriberto Seda’s cryptogram as an exercise for students of York’s cryptology course.

At the conference I also met German cryptology author Klaus Schmeh, who writes an interesting German-language blog about various cryptologic mysteries, including the Zodiac ciphers. His book Nicht Zu Knacken (which I wrote about here) has a chapter devoted to the Zodiac ciphers. At the conference, Klaus gave a talk about compiling a list of 32 encrypted books. He showed some examples, ranging from obscure encrypted texts, to more well-known books such as the Voynich Manuscript and Codex Rohonci. He even brought his own hand-made reproduction of the Codex Rohonci as a prop for people to look through.

Video of Klaus’ talk (Part 1):

Video of Klaus’ talk (Part 2):

(The volume is faint, so you’ll need to crank up the volume on your speakers)

Video game developer, cryptology enthusiast and Kryptos expert Elonka Dunin gave a talk about the use of cryptology in the recreational activity of Geocaching. I was surprised to learn that many caches require solving cryptograms and other puzzles before you can learn the location of the caches. She told me that some of the puzzles remain unsolved. You can view them here. Some puzzles are even based on the German Enigma machine.

Dr. Todd Mateer spoke about his cryptanalysis of one of the Beale ciphers. In the original document, James B. Ward’s The Beale Papers, each number in the solved cipher corresponds to a word from the Declaration of Independence. Mateer tried to reconstruct the solution based on the procedure outlined in Ward’s paper. He found that he ran in to trouble due to the numerous variations of the Declaration of Independence that were published in Ward’s day. He also found that there are mistakes in the encipherment, such as duplicate numberings in the version of the DOI in Ward’s paper. How is it that the so-called Beale cipher uses the exact same DOI variant, and the exact same encipherment mistakes, as that of Ward’s decipherment? What are the chances that Beale and Ward made precisely the same mistakes? Mateer’s conclusion is that it’s because the Beale treasure is likely to be a hoax, invented by whomever authored The Beale Papers. Nick Pelling offers the alternate view that the oddities found in the unsolved Beale ciphers reflect a change in the encipherment procedure that causes bits of an encrypted key to show through. Some experiments in this direction might help clarify his idea.

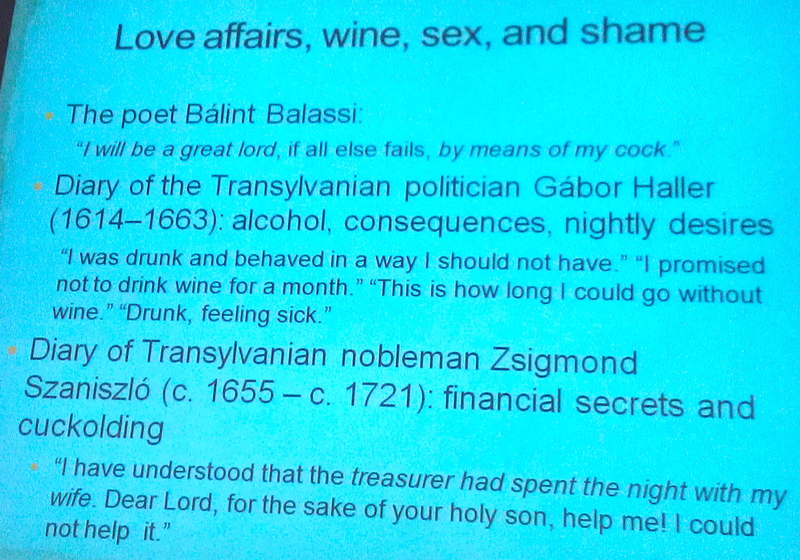

The talk with the most attention-grabbing title was Shame, Sex and Alcohol: Ciphers in the Context of Everyday Practices of Secrecy in Early Modern Times, about encrypted messages left by noteworthy Hungarian historical figures in diaries and correspondences. Here is one of the more colorful excerpts:

The conference was very educational, provoking a thirst for more knowledge and discovery. I don’t want to miss the next one in 2015!

From an upcoming natural language process conference in Seattle comes this paper from UC Berkeley: Decipherment with a Million Random Restarts.

In the paper, Berk-Kirkpatrick and Klein investigate the effectiveness of the “expectation-maximization algorithm” (EM) when it is used to search for solutions to homophonic ciphers. EM explores cipher solutions by using a statistical model of the English language. The paper describes EM getting stuck in local optima, a common problem with these kinds of automatic decipherment algorithms.

To understand the local optima problem, think of a rugged landscape. Your task is to find the largest mountain in the landscape, but you can’t see more than a few yards ahead of you. You walk around, thinking that your best bet is to find the steepest slope and follow it, You get to the top of a hill, thinking you’ve found the tallest mountain, but you’re only standing atop a medium-sized one. How can you find the tallest one?

For the EM algorithm, the answer is to randomly restart the search many times. In the rugged landscape, this translates to randomly and blindly teleporting you somewhere else in the landscape. Eventually, one of the slopes you follow will be the right one.

Zkdecrypto uses a similar approach. At each step, zkdecrypto is making small changes to a solution key, and keeping the changes that make the plain text look a little bit more like English. But it, too, might get stuck on a “small hill”: no matter what changes it makes to the key, the plain text doesn’t improve, and the real one remains beyond its reach until enough restarts are done.

Long story short: If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.

The paper tries to answer this question: How many restarts are needed to get the right solution? The researchers’ answer is that it depends on the cipher. They looked at the Zodiac’s 408, which turns out to be an easy cipher to solve: Accurate solutions are discovered without more than a hundred random restarts. Then the researchers created their own 340-character cipher, and accurate solutions were found using hundreds of thousands of restarts. They distributed the numerous restarts to the 512 computational cores of a powerful computer graphics card, an approach that is thousands of times faster than running the restarts one at a time in sequence. The increased difficulty in solving the test cipher is attributed to its smaller length, and its larger number of cipher symbols. But even with only a few hundred restarts, more than half of the correct solution to their test cipher is discovered by the program, which is usually enough for a human solver to take over and complete the solution.

The researchers unfortunately repeat the claim that in 2011, Ravi and Knight were the first to crack the 408 using completely automatic methods. Zkdecrypto has been automatically cracking the 408 since 2006.

Finally, Berk-Kirkpatrick and Klein investigated Zodiac’s 340, and mention the possibility that it may not be a homophonic cipher, or even a valid cipher whatsoever. No one even knows its proper reading order. This paper is the first I’ve seen that presents specific evidence to support the argument that the 340 is not a homophonic cipher in a normal reading order. First, the researchers generated 100 more test ciphers that are similar to the 340, and ran their EM algorithm on them with 10,000 random restarts. The result was an average accuracy of 75%, where only two ciphers had less than 51% accuracy. If the real 340 is “normal”, at least part of its message would surely have been revealed by now. When they ran their EM algorithm on the real 340, the best results were still nonsensical. They also found that the search landscape looks much different for the real 340 than it does for their test ciphers, suggesting a strong difference in its construction.

I’m curious about how closely their test ciphers resemble the real 340. Do they contain similar cyclic sequences of homophones? Do they have the weird pivots? What about spelling errors and encipherment errors, which were abundant in the 408? At this point, it seems best to try to guess what Zodiac may have done to make the cipher unsolvable. Then we can generate more test ciphers and automate their solutions. If the real 340 is constructed the same as the test ciphers, then its solution, too, will emerge.

Then again, perhaps we should heed W.C. Fields’ advice:

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Then quit. There’s no point in being a damn fool about it.

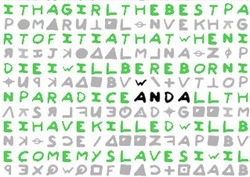

Below is contributor Chris Klein’s interesting analysis of the BTK word puzzle. He breaks down the overall puzzle into three smaller puzzles that are suggested by the appearance of clean breaks between major words and the placements of the letter “X”.

Puzzle 1:

Notes:

- This puzzle lacks numbers.

- The locations of the red X‘s suggest puzzle boundaries.

Puzzle 2:

Notes:

- The locations of the red X‘s suggest puzzle boundaries.

- In row 1 column 7 there appears to be a missing number. The letters R, A and D are near this missing number.

Puzzle 3:

Notes:

- The locations of the red X‘s suggest puzzle boundaries.

- In row 11 column 3 there appears to be a missing number. The letters E and R are near this missing number.

- This puzzle lacks numbers.

- Very many of this puzzle’s letters are used in words.

I believe that the X‘s are some type of directions for the orientation of the three puzzles.

Notes about each puzzle and final summary.

Summary:

Each of the puzzles has its own theme with regard to the hidden words within. The theme of each puzzle is as follows:

- Puzzle 1 ‐ Recon

- Puzzle 2 ‐ Location

- Puzzle 3 ‐ Method of operation

- Puzzle 4 ‐ Identity?

In each puzzle I did the following:

- Isolate all obvious words by color (yellow).

- Isolate all sequential and repetitive keystrokes that were not part of an obvious word by color (green).

- Isolate all “X”s that were non‐sequential by color (red). (I was drawn to isolate the “X”s separately because of the somewhat uniform location of the “X”s throughout the puzzles.

- Isolate all remaining, apparently random, keystrokes by color(purple).

- Isolate all numbers by color (blue). (I took some liberty here. In the “original” document that I worked from, the numbers were oddly spaced so that they were near adjacent alphabetic keystrokes. I noticed that for every oddly placed number there was a blank space to its left. I shifted the numbers to the blank spaces to the left. After doing this I noticed there were 2 blank spaces left on the chart. Interestingly the blank space in puzzle 2 is surrounded by the letters R, A, D. The blank space in puzzle 3 is preceded by E, R.

- In looking at the progression of the 3 puzzles it seems as if the creator became more efficient as he completed each puzzle. Puzzle 1 seems to have a lot of non‐sequential letters that don’t appear to be part of any hidden words whereas puzzle 3 has very few non‐sequential letters that aren’t part of any obvious words. One question I would ask is why the creator didn’t use sequential letters in puzzle 3 in certain places. Maybe there is no reason but there are only (5) non‐ sequential letters that aren’t part of any obvious word and it seems it would have been easy enough to replace those with some other letter.

- I did not go into the meanings of the different numbers on the chart.

Puzzle 1 ‐ Recon

This puzzle contains no numbers and seems to be pretty uncomplicated.

Puzzle 2 ‐ Location

This puzzle seems to be uncomplicated at first but unlike the previous puzzle it contains sets of numbers. It also contains 3 “X”s on or near the same locations as puzzle 1. This puzzle also contains a blank space adjacent to the letters R,A,D.

Puzzle 3 ‐ Method of operation

This puzzle appears to be the most detailed of the 3 puzzles. Unlike the previous puzzle there are no numbers but there is a blank space again. This blank space is preceded by the letters E, R. It also contains 3 “X”s on or near the same locations as puzzles 1 and 2.

Puzzle 4 ‐ Identity?

Not sure if one would say that all of these puzzles are just parts on 1 main puzzle but I like to consider them separately. That said, I believe the RADER name is announced by the blank space in puzzle 2 and the blank space in puzzle 3. If that were true then I would consider the grouping of puzzles 2&3 to be a separate puzzle and have labeled it as such.

Anyhow, thats what I have.

Thanks, Chris!

Recent Comments